Destroying Possible Contamination on Mars Sample’s Return to Earth

By Bethany Augliere

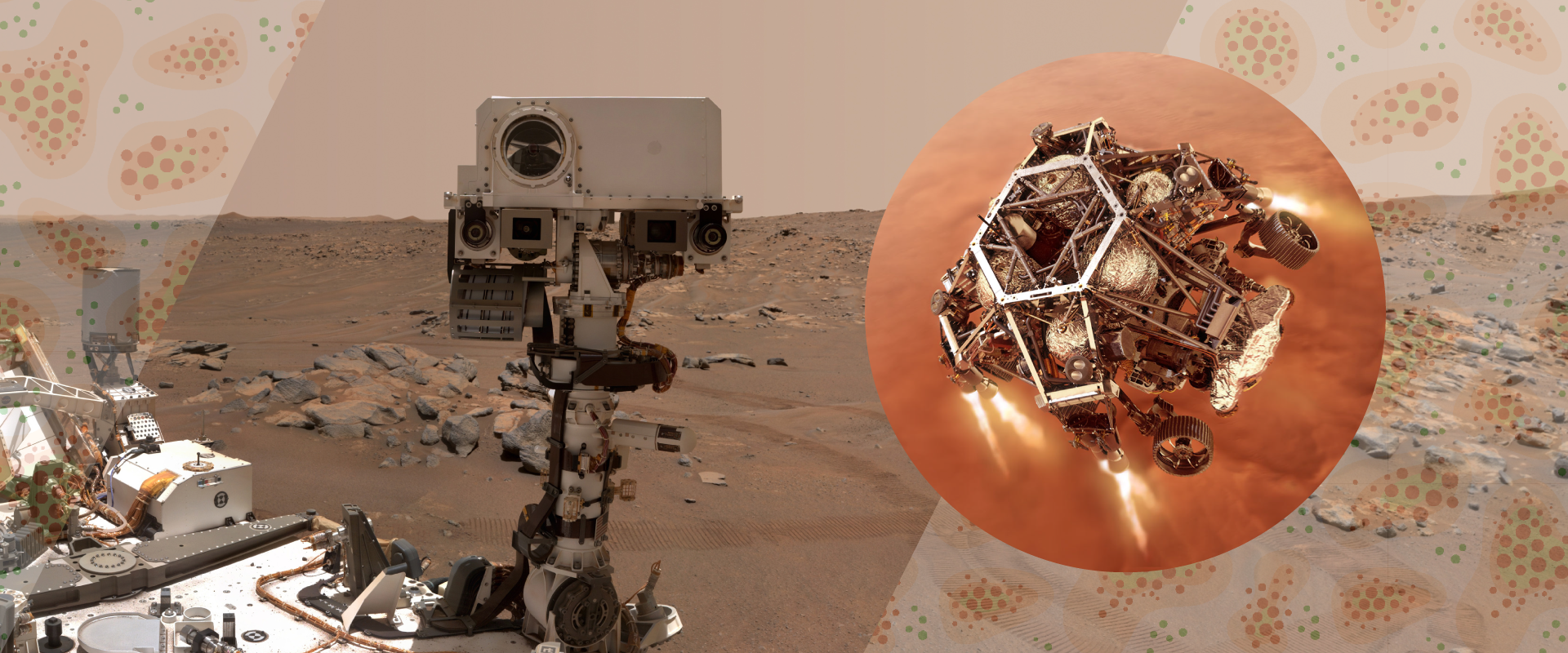

In July 2020, NASA’s Perseverance rover was launched to Mars. Upon landing Feb, 18, 2021, it’s goal became to look for past and present signs of life. When samples obtained by the rover return to Earth, Gregg Fields, Ph.D., is part of a team to help understand how to break the chain of contact with the Martian environment, ensuring all Martian material is contained and no possible stowaways survive the journey to Earth.

“While the risk is extremely low of any uncontained material, one wants a well-developed and highly effective approach to ensure the neutralization of hypothetical stowaways,” said Fields, executive director of FAU’s Institute for Human Health and Disease Intervention, and professor in the department of chemistry and biochemistry, Charles E. Schmidt College of Science.

The car-sized rover landed in the Jerezo Crater, a 28-mile-wide basin located in the planet’s northern hemisphere. Experts believe that around 3.5 billion years ago, a river flowed into a body of water about the size of Lake Tahoe, which straddles the border of California and Nevada. This is one of the best places to search for signs of microbial life, as the ancient river could have collected and preserved organic molecules, according to NASA.

While the rover searches, it will use up to 43 sample tubes, most of which are set to return to Earth as early as 2031, as part of the Mars sample return campaign being planned by NASA and the European Space Agency. The spacecraft is equipped with seven instruments, 25 cameras — the most ever in deep-space exploration — and even a helicopter the size of a tissue box to take aerial images.

Before the rover was ever even sent to space, NASA and its engineers worked hard to prevent Earth’s microbes from potentially contaminating Mars. That way, scientists also know that any potential discovery of life did in fact, originate on the red planet. Upon the samples’ return, now the goal is to ensure that no uncontained or unsterilized material is returned to Earth.

Prior to FAU joining the team, the three laboratories working on this potential problem include the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory based out of California, Nelson Laboratories headquartered in Utah, and Johnson & Johnson based in New Jersey. In June 2021, when they needed complementary techniques for the analysis of proteins and their degradation products, they reached out to Fields, whose laboratory has studied protein behaviors for more than 30 years.

Currently, the idea is to seal the sample tubes in two redundant containers. This includes heat sterilization of the joint between the halves of the primary container at a temperature high enough to break down any external organisms or proteins. The question is what temperature is required and for how long.

"While the risk is extremely low of any uncontained material, one wants a well-developed and highly effective approach to ensure the neutralization of hypothetical stowaways."

— Gregg Fields, Ph.D.

To test this, the other laboratories send Fields heat-treated samples of a yeast prion protein. Then, Fields’ laboratory uses a combination of analytical techniques, such as mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography, to look at how much of the protein sample has broken down. So far, he’s tested the protein treated at 350- and 450-degrees Celsius (662- and 842-degrees Fahrenheit) and will ultimately test protein samples treated at 500-degrees Celsius (932-degrees Fahrenheit).

“500-degrees Celsius has been specified as the sterilization parameter, but my laboratory’s ongoing work provides possible flexibility if needed in engineering parameters,” Fields said. The goal is to break the proteins down into the amino acid components, which are the building blocks of proteins.

As the samples are expected to return to Earth in about 10 years, Fields has time to continue experimenting. “Do I actually believe there are dangerous microorganisms and proteins on Mars,” Fields asked? “No, I really don’t. But we still have to protect against it by behaving at all times like there could be a hazard.”